My colleague Satu Tuominen’s recent blog (in Finnish here) discussed exercise and the role of alcohol when trying to make fitness gains and ensure sufficient recovery. I will translate and quote the highlights of her blog here and add some additional reflection and viewpoints. The basic premise of her blog is that training, especially high-intensity or high-volume training, naturally loads the body and puts special demands on recovery. ”If the goal is to improve fitness and performance, hard training must be matched with good recovery. Good recovery is ensured with sufficiently long sleep and high-quality nutrition – and avoiding extra stressors, such as stress, hurry, alcohol and drugs, stimulants, unhealthy food and mental / emotional strain.” The topic is relevant for top-level athletes, recreational athletes as well as regular people interested in their fitness, and is a common point of discussion in our work as wellness professionals, where we coach people who are trying to balance the demands of work, family, exercise, and recovery.

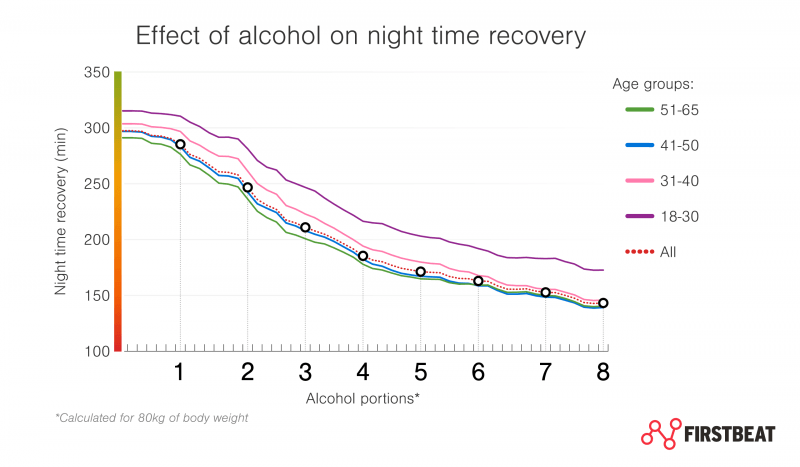

Satu continues: “One of the most significant factors known to have a negative effect on our recovery is alcohol. While most athletes and fitness enthusiasts probably know that they should not train when hungover, they might not realize that partying can actually cancel out the benefits of already conducted or upcoming training sessions. A scientific study conducted based on the Firstbeat database shows that already 2 units of alcohol reduce the amount of recovery during sleep, and when the amount of alcohol increases, the negative effect potentiates (Figure 1). Even if alcohol can help you fall asleep, it increases the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, or the amount of stress reactions during sleep. At the same time, activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, which enhances recovery, is weakened. Firstbeat Lifestyle Assessment’s stress and recovery measurement shows the increased activation level of the body very concretely.”

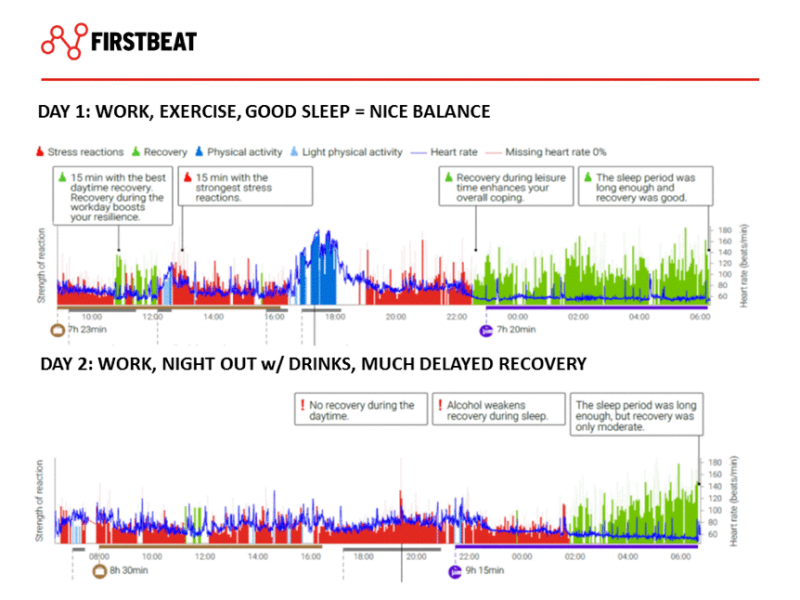

The message seems to carry across countries and cultures when we conduct our 3-day assessment to management and employees around the world: people who are interested in their well-being and fitness respect data and facts – and the sobering realization that optimal recovery and use of alcohol are rarely a good match, especially when a heavy fitness routine is part of the mix. A recent assessment to an international corporate client of mine demonstrates this well. The top graph shows that he recovered well after an evening workout (this was a routine, moderate-intensity workout for him), but the following night, after an evening out and 4 alcoholic drinks, his heart rate stayed elevated for several hours and his recovery time was cut to half. This is a typical finding and a good eye-opener, although people often find it surprising how much their sleep is compromised after just a few drinks. If exercise and drinks had been consumed on the same night, the effect had likely been even more dramatic.

Figure 2. This recreational athlete recovers well after his evening workout, but the following night, after 4 drinks, he only starts to show good recovery after 4 hours of sleep.

Satu’s blog digs deeper: ”In addition to the effects on the autonomic nervous system, alcohol reduces the amount of REM sleep, which is important for the brain and motor learning. Similarly, protein synthesis – a key function that allows muscular growth – is weakened by alcohol. Therefore, alcohol is not a good post-exercise recovery drink. Regularly consumed, already 2-3 units of alcohol in the evenings can reduce the amount of high-quality recovery during sleep enough that the body’s overall recovery is compromised.”

For a practical tip, Satu emphasizes that “if you feel like partying once in a while, you do not need to feel like it will ruin your fitness goals and gains. However, when you do that, it’s best to skip intensive training for a few days because recovering from the party takes some time and during that time, hard training is likely to do more harm than good.”

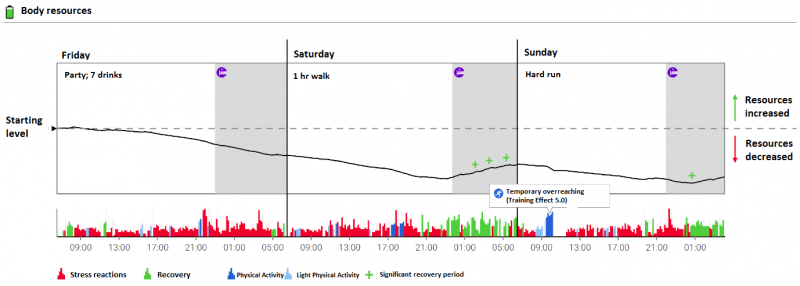

This is nicely demonstrated in Figure 3: no recovery the night after a party, followed by a moderate workout the day after, with some recovery, and a hard run 2 days later, with very little recovery. The overall effect on the body’s resources was consuming (the line keeps going down instead of climbing), and it was unlikely to contribute positively to his fitness development. The benefits of the hard run were “reversed” by poor recovery. It’s also good to keep in mind that the implications of hard exercise within 1-2 days of heavier drinking can go beyond hurting your fitness development – into being a health risk, especially when other risk factors are involved (e.g. blood pressure, cholesterol, overweight, stress, jetlag, being middle-aged or older). The ‘night out’ in itself is a heavy stress on the body (and the heart) – and should not be mixed with the heavy physical stress of exercise the day after.

Figure 3. After heavier partying, it’s best to skip intensive training for a couple of days to avoid an increased risk of overload or injuries. Recovery is significantly reduced the 2 nights after the party.

Satu’s blog concludes with a reminder that “we should not forget to enjoy life, as long as we are aware of the consequences. A couple of glasses of wine, or a heavier party occasionally, might temporarily make your workouts less effective, but they are not going to prevent or hurt your fitness improvement in the long run, as long as you follow a well-balanced training plan and healthy lifestyle the rest of the time.” I totally agree – let’s remember a principle of moderation, but be aware that in this context, moderation is not much; even a couple of drinks start compromising recovery. This is especially important when you try to optimize your recovery during more intensive training periods. And when you are faced with other stressors, such as heavy travel or high workload, think twice about potentiating the overall load with intensive training and alcoholic drinks.

If you liked this article, you should subscribe to our mailing list.

You might also be interested in

Intensity Is Your Fitness Friend

You may have heard that your fitness level is determined by your genetics. This is true. Luckily, that’s not the whole story. Experts say that about half of the variation in physical fitness between individuals is heritable, meaning it comes to you through your parents.

Reflection on My Dry January: Did It Make a Difference?

In Finland, 20-30% of adults take part in alcohol-free January. I decided to test this myself, collect some data and see how an alcohol-free month affects me. Would I notice some benefits, such as increased energy, better sleep, or even improved heart rate variability (HRV) during sleep?

Firstbeat database reveals UK’s least stressful work day and most stressful month

Key points: Study utilizes over 18,000 monitored days in the United Kingdom from real-world conditions Heart rate variability (HRV) offers objective insights into periods of stress and recovery Monday is…